The Helen de

Leeuw legacy: redesigning South Africa.

Curated by Juliette Leeb-du Toit (VIAD

Research Associate)

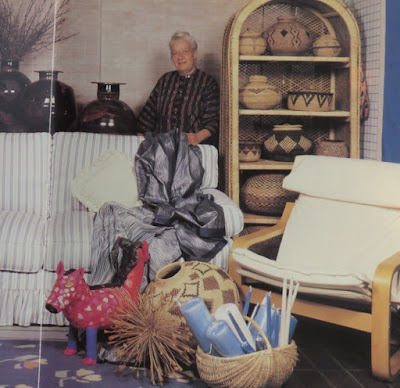

In the proposed

Helen de Leeuw legacy exhibition, tribute is being paid to a phenomenal woman

entrepreneur, ceramicist and writer, Helen de Leeuw, who in the 1950s began a

lifelong challenge to the South African market to rid itself of erstwhile

preferences (both anglophile and American) for mass-produced, inferior products

that had begun to overwhelm commercial production and suppress emergent and indigenous

craft traditions.

Few urban South

Africans who lived through the period 1953 to c1988 will fail to recall the

impact of the Helen de Leeuw phenomenon. Writing in 1965, Isobelle du

Toit noted that Helen de Leeuw’s name was synonymous with ‘good,

modern and imaginative taste’ and design in all its aspects in textiles,

craftwork, architecture, furniture, interior design, jewellery and ceramics. De

Leeuw’s stores in effect functioned as galleries of contemporary international

and national design.

Reflecting her vast

and accruing knowledge of avant-garde post-war design from Europe, especially Finland,

de Leeuw‘s galleries were in many ways an extension of herself, her taste and

preferences. To her design was no longer to be dictated from above, but was

ideally eclectic, idiosyncratic and flexible. Her stores were

typified by an uncanny aura of the authenticity that she craved – they

contained articles of natural materials that were well designed and unusual.

Articles were selected because they

were handmade, reflected care and craftsmanship, and had ‘an honesty’ that she appreciated.

She embraced locally produced items that reflected this as well as imports,

drawn to countries that have a ‘craftsman approach’ and was among the first to

include indigenous ceramics and beadwork in her galleries.

She was the first to

exhibit local pottery such as the work of Esias Bosch, Andrew Walford and

Liebermann ceramics, exhibiting their work alongside that of Arabia,

Arzberg and local Zulu and Venda wares

in an eclectic mix that came to mark shifting, culturally inclusive post-war

South African preferences.

As the doyenne

of what was described as ‘modernist design’ in all its aspects, Esme Berman noted: ‘Helen de Leeuw has been

responsible more than any other single person in South Africa for developing in

the public a sound taste and a feeling for good design and craftsmanship’. (The

Star, 4 Aug 1980).

In this

exhibition the gallery will partly replicate aspects of her Craftsman’s Market

interiors to reflect the diversity of her design preferences in photographs as

well as a collection of items sourced originally in her commercial outlets. We

would like to encourage those who have items acquired from De Leeuw to consider lending these for inclusion in

the exhibition. If you have any

particular information regarding De Leeuw that you would care to share with the

curatorial team we would be pleased to have you contact us at leebdutoitj@gmail.com

Curated by Marlize Groenewald.

Ernst de Jong

was born in 1934, in Pretoria, South Africa. In 1951, he was awarded an

athletic scholarship to the University of Oklahoma (OU), in the USA. Here he pursued a degree in Fine Arts

(majoring in Information Design) and was taught by, amongst others, John

O’Neill — known for his abstract imagery and early modern style — and Emilio

Amero, a leading figure of the Mexican modern art movement. Beyond the

classroom, de Jong encountered the work of creative practitioners such as Ben

Shahn and Saul Steinberg, who merged commercial illustration with fine art

practice. He was introduced to the workings of the local petroleum industry, an

eclectic mix of cowboy and American Indian culture, as well as the

transformative project, spearheaded by Governor Raymond Gary, of Oklahoma from

a bucolic backwater to an industrialised, ‘modern’ state.

In 1955, de

Jong married Gwendolyn Drennan, a fellow student at OU, and in 1957 the couple

returned to South Africa. In 1958, both de Jongs secured lecturing positions at

the Art School of the Pretoria College for Advanced Technical Education. The school, under the directorship of Albert

Werth, was, in Gwen de Jong’s words, staffed by ‘quite an extraordinary bunch

of people’ who sought to engage with the domestication of modernism in a

peripheral, African community. The emphasis was on craft. Colleagues included

Peter Eliastam, who along with the de Jongs taught applied design; Zakkie Eloff

who taught portraiture; Robert Hodgins, painting, life drawing and basic

design; Leo Theron, mosaic; Maxie Steytler, fabric painting and design; Carol

Hamilton, history of art and architecture; and Dulcie Campbell, ceramics.

Although de

Jong’s primary aim was to construct a reputation for himself as a painter, his

contribution to the field of design is, arguably, his greater legacy. In the

opinion of former students, he pioneered the idea of graphic design as a

profession in Southern Africa. He would also be instrumental in the

implementation of the first university degree in Southern Africa that

acknowledged the discipline of information design. Realising that there was a

shortage of design skills in the then Transvaal, he opened his own design

consultancy, Ernst de Jong Studios (EDJS), in 1958.

The studio, situated across the road from the Pretoria College, recruited top graduates and executed commissions that, in their number, variety and reference to American modernism, set the de Jongs apart as exciting ‘new stars’. The studio acquired legendary status, not least because its director was held in awe as the local ‘Afrikaans’ boy who helped steer South Africa into the rarefied world of international design trends.

In 1987 de Jong received the once-off Dashing Society of Designers of South Africa Crystal Award for Outstanding Design Achievement. Finally, in 1994, after directing the collaborative project of designing South Africa’s iconic ‘Big Five’ bank note series, de Jong closed EDJS in order to travel, teach and paint.

The studio, situated across the road from the Pretoria College, recruited top graduates and executed commissions that, in their number, variety and reference to American modernism, set the de Jongs apart as exciting ‘new stars’. The studio acquired legendary status, not least because its director was held in awe as the local ‘Afrikaans’ boy who helped steer South Africa into the rarefied world of international design trends.

In 1987 de Jong received the once-off Dashing Society of Designers of South Africa Crystal Award for Outstanding Design Achievement. Finally, in 1994, after directing the collaborative project of designing South Africa’s iconic ‘Big Five’ bank note series, de Jong closed EDJS in order to travel, teach and paint.

Within the

context of its thirty-six year existence, it is impossible to convey in any

detail the breadth and relevance of the output of EDJS. In this sampling of the

studio’s work and the style that de Jong favoured in his project of

‘modernising’ the nation (and perhaps, most particularly, white, middle-class

Pretoria), the emphasis is on de Jong’s environmental graphics. Although

additional material provides a context for the display, the exhibition lifts

out de Jong’s earliest commissions, such as the design and construction of show

stands for exhibitors at industrial expositions in Pretoria and Johannesburg.

This selection provides a link to the spatial nature of the accompanying exhibition of Helen de Leeuw’s modernising rhetoric that evinces interesting parallels of circumstance and purpose with that of de Jong. Both individuals could be said, as Chris Barron claims for de Leeuw, to have ‘created an alternative way of living for … South Africans suffocating in a stuffy aesthetic inherited from the British colonial past’.

This selection provides a link to the spatial nature of the accompanying exhibition of Helen de Leeuw’s modernising rhetoric that evinces interesting parallels of circumstance and purpose with that of de Jong. Both individuals could be said, as Chris Barron claims for de Leeuw, to have ‘created an alternative way of living for … South Africans suffocating in a stuffy aesthetic inherited from the British colonial past’.